People learning from example and Eucharistic thanksgiving — once quite common — is a Catholic custom that we simply don’t see modeled very often anymore.

But we can embrace examples from our past, reignite worthwhile spiritual practices, and model them for our children and for future generations. Just like someone did for my mom, many years ago.

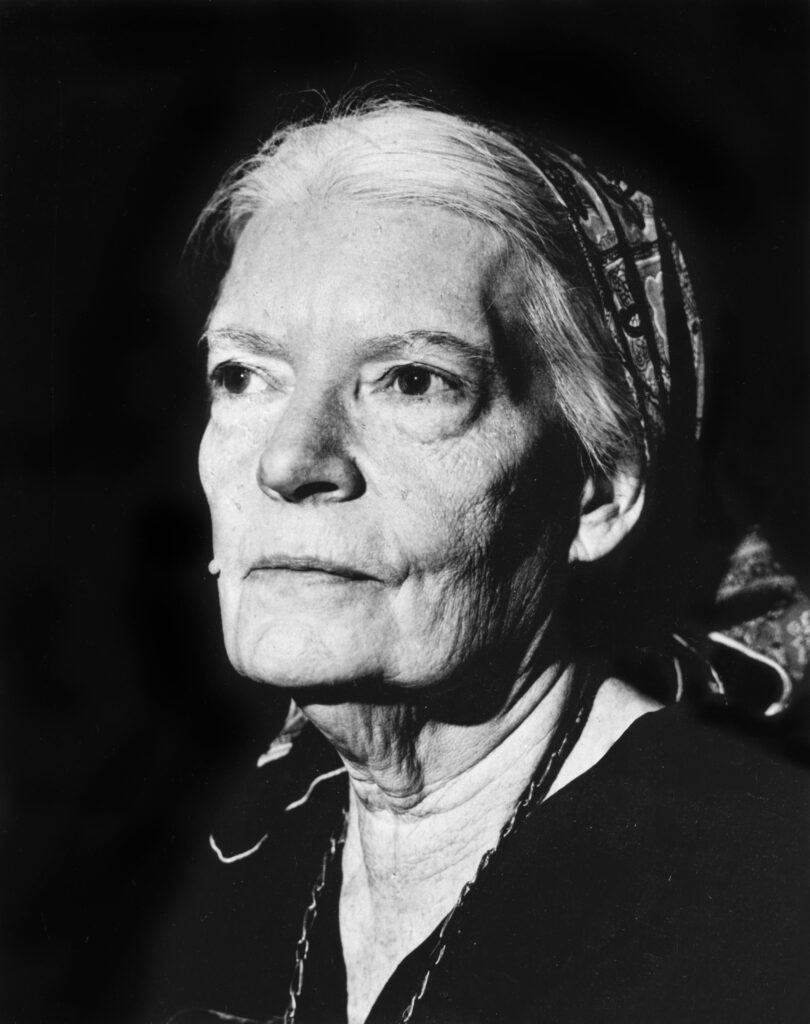

In 1977, my then 20-year-old mother visited the Catholic Worker in New York City, together with a religious sister. The two were in the process of helping found a Catholic Worker house in Rochester, New York, and how better to learn than through the example of Maryhouse, the women’s shelter founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin?

Now a Servant of God, Day was a powerful force during her lifetime, and her example of fervent Catholicism inspired my mother. With the force of youth, my mother was determined to meet her heroine.

She and her friend arrived on Friday and spent Saturday observing how Maryhouse functioned. By Sunday, my mother hadn’t yet fulfilled her ambition to meet Day. Having gone to a vigil Mass the previous evening, she decided to park herself on the stair landing inside Maryhouse and simply wait for the woman to show up.

Three hours later, quite discouraged, she was ready to leave her post.

Then it happened! Just as Mom was about to abandon her watch, Dorothy Day — looking frail and thin, but carrying an undeniable aura of holiness about her — stepped through the door. Day clearly seemed “someplace else.” Not thinking that the holy woman might be deep in prayer, my excited mother jumped up and introduced herself.

Who knows what Day might have thought about this young woman’s boldness, but very kindly and quietly she explained to my mother, “I would talk to you right now, but I’m coming from holy Communion, and I’m in a spirit of thanksgiving.”

It was the first time someone had ever said such a thing to Mom or provided an example of what Eucharistic thanksgiving looked like. While she was raised in a devout household and spent much of her time surrounded by priests and nuns, she’d never seen such a display of Eucharistic gratitude.

The encounter was permanently imprinted on her memory. Dorothy Day was herself a bold woman, one who knew her own mind and that mind was completely conformed to Christ, absent of all ego.

“Maybe I should have that,” my mother thought to herself.

While they never had the conversation my mother hoped for, she’d still encountered Day in a profound moment of personal witness and example, one that never left her.

In subsequent years, my mother realized Day must have walked from the church back to Maryhouse — through the bustle and noise of one of the busiest cities in the world — in complete interior focus and adoration of Jesus Christ. How much discipline it took to be able to shut out the city entirely and give thanks, carrying Christ with her on that journey home.

Dorothy Day passed away three years later, while living in Maryhouse, having left her mark on society and on my mother, who went on to help run the first Catholic Worker house in Rochester. The emergency shelter for women and children was the first of five houses that she helped found. She dedicated her time to the Catholic Worker before getting married and raising five children, with the example of Dorothy Day being ever-present for her, even now.

“I tried to emulate her example, however imperfectly, in the circumstances I found myself — in the opportunities presented to me,” Mom once told me.

Thus, an earnest outreach during an unintentional interruption of holy prayer was the powerful catalyst for her own lifelong, quiet journey with Catholic social action and within Eucharistic intimacy.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church tells us clearly that, “the Eucharist is a sacrifice of thanksgiving to the Father, a blessing by which the Church expresses her gratitude to God for all his benefits” (No. 1360). Yet too often, perhaps in our well-intended haste to be a more social church, Mass has become something to rush out of so we might grab a coffee in the parish hall, or have a catch-up chat in the aisle. While fellowship is crucial to a thriving church, Eucharistic thanksgiving fades away amid all that activity.

There is a famous story of the 16th-century saint Philip Neri. While celebrating Mass he noticed a man receiving Communion and leaving early. He sent two acolytes to follow the man, bearing lighted candles. Confused, the man returned and asked Neri why he’d sent the acolytes. Neri responded, “We have to pay proper respect to Our Lord, whom you are carrying away with you. Since you neglect to adore Him, I sent two acolytes to take your place.”

Whether it’s the 16th century or the 21st, we have models of what Eucharistic thanksgiving looks like. Particularly as we move more deeply into this time of Eucharistic revival, perhaps some of us ought to take up the practice and see what happens. Perhaps we can lead by example — by modeling gratitude in this way so others can think to themselves, as my mother did, “Maybe I should have that.”

– – –

Adele Chapline Smith writes for OSV News from New York.

By:

Steven Schwankert

| 09/18/2025

By:

Steven Schwankert

| 09/18/2025

By:

Mary Shovlain

| 09/18/2025