The Archdiocese of New York at 175: An Introduction

By: The Good Newsroom

On July 19, 1850, Pope Pius IX recognized that the Diocese of New York deserved to become an archdiocese

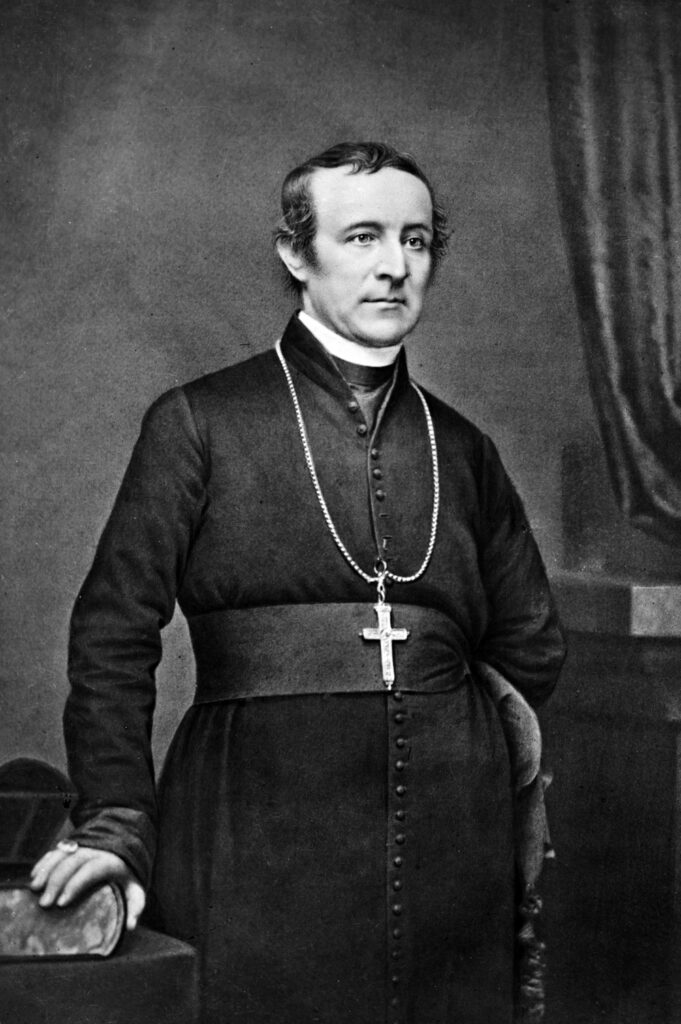

On July 19, 1850, Pope Pius IX established the Archdiocese of New York, a significant development in the city and the area’s Catholic history. The archdiocese’s first archbishop was the colorful and controversial John Hughes.

In 2000, the late historian Monsignor Thomas J. Shelley commemorated the 150th anniversary of the archdiocese for Catholic New York, highlighting the times, New York City’s immigrant population, and the first Archbishop of New York who made it the most important archdiocese in the country. The Good Newsroom is pleased to celebrate the 175thanniversary of the archdiocese by serializing that history throughout the week of July 14-18. The text has been updated slightly to reflect the passage of time.

July 19 is an important anniversary for New York Catholics. On that day, 175 years ago, Pope Pius IX recognized that the Diocese of New York had grown to such an extent since its founding in 1808 that it deserved to be an archdiocese. As a result, on July 19, 1850, the Holy Father formally established the Archdiocese of New York. At the same time, he appointed Bishop John Hughes the first archbishop. Ever since that date, the man and the archdiocese have been inseparably linked.

In 1850, John Hughes was no stranger to New York. At that point, he had already been a resident of the city for 12 years. An Irish immigrant who was ordained a priest of the Diocese of Philadelphia in 1827, John Hughes first came to New York in 1838 to serve as coadjutor bishop to the aging Bishop John Dubois. The following year, after Dubois suffered a series of debilitating strokes, Hughes was appointed apostolic administrator of the diocese. Then, upon the death of Dubois in 1842, Hughes automatically succeeded him as the fourth Bishop of New York.

When the Holy See established the Archdiocese of New York on July 19, 1850, it was not only an acknowledgment that America’s largest city deserved to be the site of an archdiocese, but also a vote of confidence in Bishop Hughes. By that date, Hughes was already a national figure, the first Bishop of New York to achieve such prominence. He was, in the words of one of his biographers, Henry Browne, “the best known, if not exactly the best loved Catholic bishop in the country.” On the local level, he had already performed wonders in bringing order and discipline to a chaotic diocese.

History From Above and Below

Today, the Great Man approach to history is neither politically correct nor academically fashionable. For a long time, American Catholic history was rightly criticized because it was written almost exclusively from that narrow perspective. In the case of New York Catholic history, Professor Jay P. Dolan of the University of Notre Dame provided a needed corrective a quarter of a century ago with his pioneering work, “The Immigrant Church: New York’s Irish and German Catholics, 1815-1865.” It was a refreshingly different kind of Church history. As the subtitle of the book indicates, it is history written from below rather than from above.

More specifically, it is Church history from the perspective of the people in the pews rather than that of the bishops. Dolan’s book has since become something of a minor classic in the field of American Church history. It is still in print as an inexpensive paperback from the University of Notre Dame Press and is an invaluable guide to the history of antebellum Catholic New York.

However, one needs only look in the index of “The Immigrant Church” to see how John Hughes dominates the story for the last 25 years covered by Dolan’s book. Even in a work that was deliberately designed as social history rather than episcopal biography, John Hughes emerges as a bigger-than-life figure. “In New York, no one had to ask who ruled the Church,” Dolan explained. “John Hughes was boss…. He ruled like an Irish chieftain.” That meant that his style was not dialogic. When two Irish-born priests complained to him that he had violated their rights in canon law, Hughes shot back that “he would teach them County Monaghan canon law and send them back to the bogs whence they came.” Father Ambrose Manahan, an eccentric New York priest who occasionally felt Hughes’ wrath, once described him as “a tyrant, but with feeling.”

John Hughes did not single-handedly make New York the largest and most important archdiocese in the United States. Historians like Jay Dolan have filled in the picture for us by identifying many of the less prominent men and women–lay, religious, and clerical–who made vital contributions to the shaping of New York Catholicism. Nonetheless, it is hard to believe that the story would have unfolded as it did without the raw energy, determination, and courage of John Hughes. For better or worse, he put his stamp on the Church in New York as no one else has done before or since. To be sure, there is more to the story of New York Catholicism than John Hughes, but it is not a bad idea to begin the story with him.