The Archdiocese of New York at 175: New York's Immigrant Church

By: The Good Newsroom

When John Hughes came to New York in 1838, the Diocese of New York included all of New York state and the northern half of New Jersey, an area of 55,000 square miles, with about 200,000 Catholics

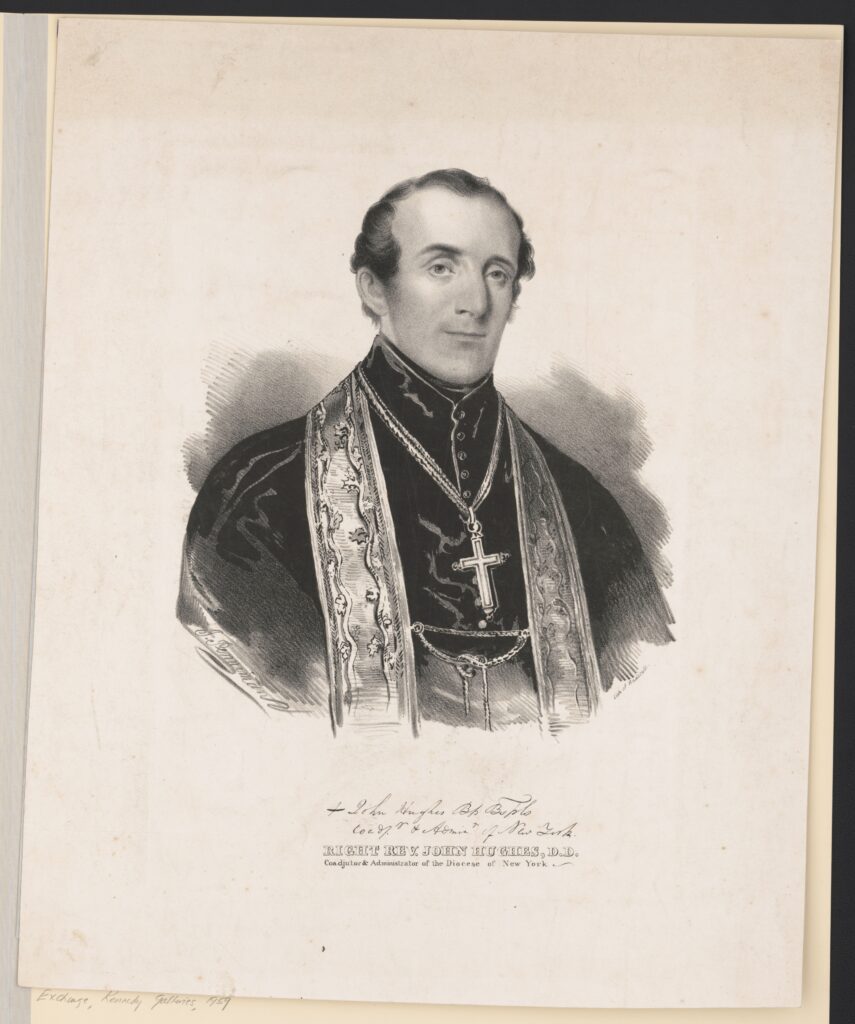

On July 19, 1850, Pope Pius IX established the Archdiocese of New York, a significant development in the city and the area’s Catholic history. The archdiocese’s first archbishop was the colorful and controversial John Hughes.

In 2000, the late historian Monsignor Thomas J. Shelley commemorated the 150th anniversary of the archdiocese for Catholic New York, highlighting the times, New York City’s immigrant population, and the first Archbishop of New York who made it the most important archdiocese in the country. The Good Newsroom is pleased to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the archdiocese by serializing that history throughout the week of July 14-18. The text has been updated slightly to reflect the passage of time.

When John Hughes came to New York in 1838, the diocese was 10 times the size of the present-day Archdiocese of New York. It included all of New York state and the northern half of New Jersey, an area of 55,000 square miles, with about 200,000 Catholics. In that extensive diocese, there were only 38 churches and 50 priests, two Catholic schools, and a few orphan asylums. There was not a single Catholic college, seminary, rectory, hospital, or other institution. “The churches were too few,” said Hughes, “and these [were] in debt to an amount greater than they would have brought at public auction.” Moreover, Hughes added: “The people were too poor and for a long time the increase of their numbers only added to their poverty as emigrants arrived in our port from Europe penniless and destitute.” The plight of the Irish famine victims was especially pitiable. “The utter destitution in which they reached these shores,” said Hughes, “is almost inconceivable.”

New York City underwent a major transformation during the quarter-century that John Hughes headed the Church in New York. In 1838, 14th Street was the northern boundary of the city. During the next 25 years, a whole “new city” grew up between 14th Street and 42nd Street with almost 200,000 additional people. The total population of the city approached 800,000. At the time of Hughes’ death in 1864, one out of every four New Yorkers was born in Ireland, and one out of every six New Yorkers was born in Germany. Thanks to this massive immigration, Catholics probably constituted half of the population of the city. By that date, new dioceses had been created in Buffalo, Albany, Newark and Brooklyn, reducing the size of the Archdiocese of New York to its present boundaries. Nonetheless, even within the limited confines of the archdiocese, John Hughes faced the daunting challenge of caring for a Catholic population that numbered 400,000.

Most New York City Catholics of that era were poor immigrants. The Irish were concentrated in lower Manhattan, especially in the Sixth Ward, the “Bloody Auld Sixth,” as it was called, where it was alleged that there was one grog shop for every six inhabitants. It is a matter of dispute among historians whether these Irish Catholic immigrants were regular churchgoers, but there can be no doubt about their generosity to the Church despite their extreme poverty. Many lived in rickety tenements without adequate light or sanitation that stood next to slaughter houses, stables, and breweries. The men found work as day laborers, stage-coach drivers, construction workers, or longshoremen, while the women often were employed as domestics. Most of the clergy who ministered to them were also Irish-born, like Father John Power, the pastor of St. Peter’s Church on Barclay Street. A notable exception was Father Felix Varela, the Cuban-born pastor of Transfiguration Church on Mott Street, who was enormously popular with his Irish congregation.

The only other large Catholic ethnic group, the Germans, lived mainly in the four wards of the Lower East Side. They tended to keep their distance from the Irish and desired to have their own parochial schools, hospital, orphanage, and even a separate German Catholic cemetery. As early as 1833, they got their own German national parish, St. Nicholas on East Second Street, founded by Father John Raffeiner, the pioneer German priest in New York. Father John Neumann, who was canonized in 1977, celebrated his first Mass in the church on June 26, 1836. However, St. Nicholas Church was soon overshadowed by a second German church, the Church of the Most Holy Redeemer on East Third Street. In 1851, the Redemptorist Fathers, who administered the parish, replaced the original wooden church with the present stone building, which could accommodate 3,500 worshipers. For many years, it was the unofficial German Catholic cathedral in New York.

Ethnic rivalry sometimes flared between New York’s Irish and German Catholics. In 1847, the Redemptorists established a German church on the lower West Side, St. Alphonsus on Thompson Street. The Irish began to attend Mass there in large numbers, and the pastor noticed that they were contributing more in the collection than the Germans. When he made plans for a new and larger church, he made provision for a basement church as well. Some German parishioners objected to the inclusion of a basement church for fear that they would be relegated there. “We will not go downstairs and have the Irish over our heads,” they announced.

Neither Italians nor Hispanics nor Slavs nor Asian Catholics were present in New York in any appreciable numbers in Hughes’ day. However, in addition to the Irish and German Catholics, there was also a small French Catholic community that was sufficiently numerous to form its own Church of St. Vincent de Paul in 1841. The most famous member of this French-speaking community was not a Frenchman at all, but a black slave from Haiti, Pierre Toussaint, who came to New York in 1797, was emancipated in 1807, and became a prosperous hairdresser. A pewholder in St. Peter’s Church as well as a benefactor of the Church of St. Vincent de Paul until he died in 1853, Pierre Toussaint was well known for his generosity to the poor, especially to the children in the Catholic orphan asylum. Cardinal O’Connor introduced the cause for his canonization in 1990, and in 1997, he was declared Venerable.

This rapidly growing Catholic population created an insatiable demand for more churches, schools, and charitable institutions. In 1859, Archbishop Hughes boasted that he had dedicated 97 churches in the previous 20 years, an average of one new church every 10 weeks. In the area that remained part of the archdiocese, he established no fewer than 61 new parishes. Some of the city parishes served huge numbers of people. At St. Stephen’s Church on East 28th Street, 10,000 people attended Mass every Sunday. In addition to the parish, the pastor, Father Jeremiah Cummings, and his single curate were responsible for the care of 1,000 Catholic patients in Bellevue Hospital.

Education was a major priority for Hughes, “the subject of all others that he had nearest his heart,” according to his secretary and biographer, John Hassard. By 1864, three-quarters of the parishes had parochial schools, 12 of them “select” schools that charged tuition, and the other 31 “free” schools. Both these schools and the growing number of Catholic charitable institutions depended for their existence on the religious communities of men and women who staffed them. In 1838, there was only one religious community in the diocese, the Sisters of Charity of Emmitsburg, who had come to New York City in 1817 to open the first Catholic orphan asylum. By 1864, there were 10 additional religious communities of men and women at work in New York. Most of them came at Hughes’ invitation, and their presence soon made an incalculable difference in the quality of Catholic life throughout the archdiocese.