The Archdiocese of New York at 175: The Lion in Winter

By: The Good Newsroom

At an elaborate ceremony on August 15, 1858, Archbishop John Hughes blessed the cornerstone of the new St. Patrick’s Cathedral

On July 19, 1850, Pope Pius IX established the Archdiocese of New York, a significant development in the city and the area’s Catholic history. The archdiocese’s first archbishop was the colorful and controversial John Hughes.

In 2000, the late historian Monsignor Thomas J. Shelley commemorated the 150th anniversary of the archdiocese for Catholic New York, highlighting the times, New York City’s immigrant population, and the first Archbishop of New York who made it the most important archdiocese in the country. The Good Newsroom is pleased to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the archdiocese by serializing that history throughout the week of July 14-18, 2025. The text has been updated slightly to reflect the passage of time.

Historian E.P. Spann has noted that New York City in the mid-19th century was “the capital of Protestant America.” It housed the headquarters of powerful interdenominational organizations, such as the American Bible Society, whose interlocking directorates formed the so-called Benevolent Empire. Many Protestant leaders, said Spann, “made no secret of their belief that Roman Catholicism was alien and inferior.” Undeterred either by the poverty of his own people or the prejudice of others, John Hughes decided to erect a monumental edifice in New York City that would serve as a statement that Catholics had indeed arrived in the capital of Protestant America.

At an elaborate ceremony on August 15, 1858, John Hughes blessed the cornerstone of the new St. Patrick’s Cathedral. “We propose,” he announced, “to erect a cathedral in the city of New York that may be worthy of our increasing numbers, intelligence, and wealth as a religious community.” Critics called it “Hughes’ folly” because the location was so far from downtown, but a few years later, the City Directory stated that “a more eligible location could not have been chosen for so vast and imposing a structure.” Construction of the cathedral was halted during the Civil War, and unfortunately, Hughes never lived to see the building finished. It was dedicated in 1879 by his successor, Cardinal John McCloskey, who also completed the twin steeples. Still later, Archbishop Michael Corrigan added the Lady Chapel, and Cardinal Francis Spellman renovated the sanctuary. Other archbishops of New York have embellished it in various ways, but it always will remain John Hughes’ monument. It was his vision and daring that gave New York’s Catholics “a cathedral of suitable magnificence.”

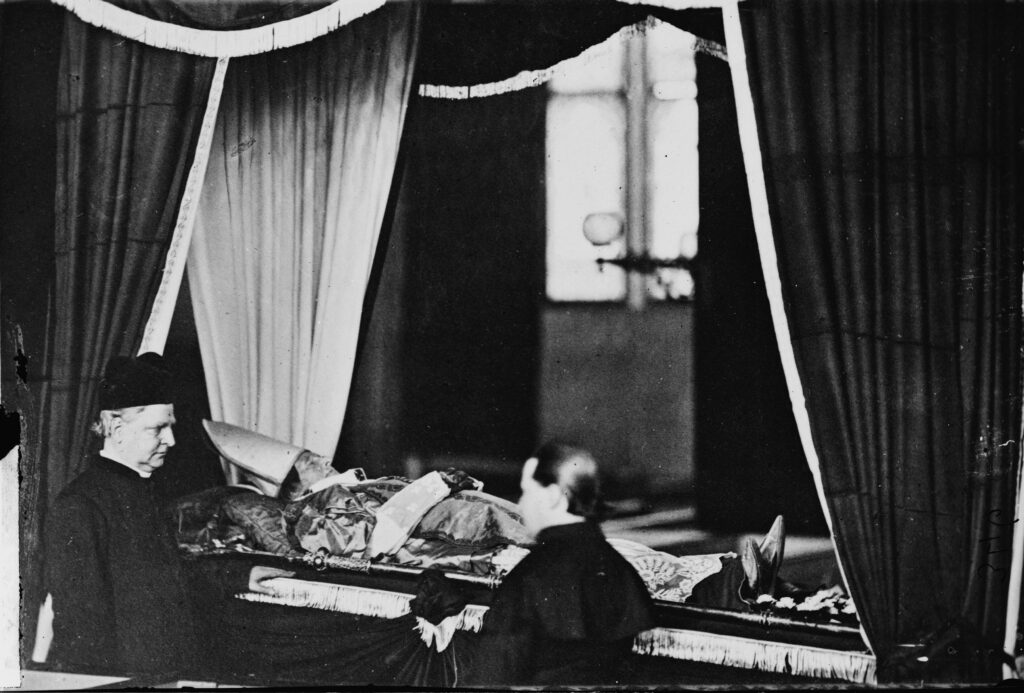

Hughes’ stature indicated that during the Civil War, at the request of his old friend William Seward, now Secretary of State, he made a trip to France on behalf of the Union cause. Like most Catholics of the northern states, the archbishop strongly supported the war to preserve the Union, but he vigorously opposed the abolition of slavery. In July 1863, anti-draft riots broke out in the city. For three days, mobs, many of them composed of Irish Catholics, roamed the city, leaving 107 dead and many wounded. Innocent blacks were the special object of the rioters’ fury. By this time, John Hughes was a dying man. However, at the request of the mayor, he made his last public appearance when he appealed for peace from the balcony of his Madison Avenue residence after the riots had been forcibly suppressed.

It is an understatement to say that John Hughes was a complex character. He was impetuous and authoritarian, a poor administrator and worse financial manager, indifferent to the non-Irish members of his flock, and prone to invent reality when it suited the purposes of his rhetoric. One of the Jesuit superiors at Fordham with whom he quarreled said, “He has an extraordinarily overbearing character; he has to dominate.” Nonetheless, through sheer strength of character, Hughes won the grudging respect of his opponents and the unconditional loyalty of the New York Irish who composed the vast majority of the local Catholic community.

The secret of his success is to be found in his ability to identify himself so thoroughly with the problems and difficulties of his fellow Irish immigrants. Born in County Tyrone in 1797, he once remarked that, for the first five days of his life, he was “on social and civil equality with the most favored subjects of the British Empire.” Once he was baptized a Catholic, however, John Hughes immediately became a second-class citizen in 18th-century Ireland. As a young immigrant without education or skills, he spent his first few years in America as a common laborer. Thus, he had firsthand experience of both the prejudice and poverty that were the common lot of the Irish immigrants of his day. He never forgot his roots and became a fearless and articulate spokesman for his people when they had few others to speak on their behalf. Governor Seward told him: “You have begun a great work in the elevation of the rejected immigrant, a work auspicious to the destiny of that class and still more beneficial to our common country.”

Like many public figures of comparable stature, John Hughes will remain forever controversial as revisionist historians debate his merits and shortcomings. Perhaps the late Monsignor John Tracy Ellis offered the most balanced assessment to date. He deplored Hughes’ bluster and lack of tact, and he admitted that John Hughes was “not what one would call a likeable character.” However, Monsignor Ellis insisted on judging Hughes in the context of his own time. Writing in 1966, he reminded a Catholic critic of Hughes that “the Protestantism of the 1840s, or for that matter, the Protestantism of the United States down almost to the present decade, was in no sense the ecumenical-minded, irenic Protestantism [that] has so radically altered its tone concerning Catholicism in recent years.” For that reason, said Ellis, “there were times when [Hughes’] very aggressiveness was about the only approach that would serve the end that he was seeking, viz., justice for his people.”

On July 19, 2025, when New York Catholics observe the 175th anniversary of their archdiocese, it is to be hoped that they will also remember their first archbishop, warts and all.